During the coldest week of the winter, a reported 130 million Americans viewed the ABC-TV dramatization “Roots” and were led to reflect in their cozy living rooms on the barbarous conditions that were imposed on blacks under chattel slavery.

Now efforts are afoot to discredit not only the grand patriarch of “Roots” – Kunta Kinte – but also the literary judgment of his grandson four times removed, Alex Haley, the book’s author.

Thanks to reporter Mark Ottoway of the London Times, who went sleuthing in the Gambian village where Haley sought his ancestral fathers, a remarkable feat of genealogical detective work is being questioned on its merits as a historical narrative.

Ottoway’s attempt to debunk the book could have a depressing effect on Juffure, the Gambian village where Kunta Kinte grew up. As a result of Haley’s narrative, the village is becoming a tourist attraction. But more is at stake in the “Roots” controversy than the economic fortunes of an African village, as important as they are.

Ottoway’s dig at the roots of “Roots” smacks of sensationalism; of a desire to unmask the book as more fantasy than fact. But his effort to reduce Haley’s chronicle to a mere myth won’t alter the symbolic truth behind the people and events depicted by Haley. “Roots” will not wither nor die.

Ottoway is within his rights to challenge, question, and seek the truth. Sound investigative journalism helped shed light on the Watergate fiasco for Americans. Yet it somehow seems absurd that a work that took over 12 years to complete should face a serious challenge from a reporter whose counter-intelligence efforts took an estimated nine days.

Ottoway’s main charge is that, in his eagerness to discover his African ancestors, Haley was the victim of a bogus “griot,” or village historian. The Britisher claims that, having been apprised of Haley’s quest beforehand, the griot obliged with “facts” to fit Haley’s dream.

Ottoway, in short, asserts that Haley learned of Kunta Kinte from a man of “notorious unreliability.” Yet cultural anthropologists have long valued the accounts of “griots” in cultures in which oral history flourishes. Village griots are not to be confused with village idiots. In cultures that rely on oral history, they have a position of real trust and status.

One should not forget that Haley’s search for his African roots began with cherished stories about “the defiant African” that were told by Haley’s relatives on balmy southern nights in Henning, Tennessee.

After diligent searching through plantation records, Haley was able to fill in most of the details of the American lives that preceded his. With the help of a linguistic expert in 1967, Haley traced his bloodline in Gambia through three African words that were used commonly and idiomatically among the villagers of Gambia.

Haley must have known how much scrutiny his book would attract, and he has offered to debate his critics on the reliability of his methods. As one who heard the author lecture in 1974 at a Midwestern college, prior to the publication of “Roots” my single most lasting impression was of the precision and consummate dedication that Haley was investing in the completion of his genealogical mosaic.

The Mark Ottoways of the world will undoubtedly persist, by their own lights, with the same sort of tenacity – and no doubt there will be critics of the critics.

As the critics attempt to uproot “Roots,” however, the sad thing will be their lack of facility in sorting out the forest from the trees. Despite minor technical flaws that some historians have found in “Roots,” the spirit of Kunta Kinte’s epic will prevail and its importance as a human chronicle will stand as tall as the California redwoods.

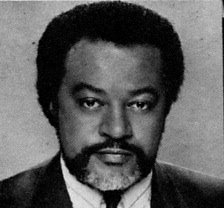

(Dennis Day is a supervisor in the Division of School Extension of the Philadelphia School District.)

No comments:

Post a Comment