(Dr. Geneva Moore is Professor of English Literature, University of Wisconsin, Madison and a dear friend of mine. Here is her tribute to my mother, Irene Day-Comer, and her music. At the left you can click through to hear my mother's recording, Touch Somebody's Life.)

Irene Day: Touch Somebody’s Life (20th Anniversary Edition)

Sunday morning. Every mature African American who attended a Baptist church remembers the sweet, significant meaning of these descriptive words: Sunday morning. On the first day of the week in East Chicago, Indiana, the Antioch Baptist Church provided its members and visitors with a deeper understanding of their identity beyond the limited secular identity imposed upon them by the world.

The spirited goal of Sunday morning was accomplished primarily through the ministry of sermons and music, especially the music of Negro spirituals, invested as they are in a spiritual legacy borne out of the poignant depths of the ancestors’ creative suffering.

From Maya Angelou to Toni Morrison, a select number of African American writers have paid tribute to soloists who performed, in their melodious voices, the necessary Sunday morning ritual of transporting African Americans into a sacred sphere. In this blessed space that literally and figuratively transformed their lives beyond the racial challenges and the tedium of daily life, African American worshippers experienced a weekly rebirth.

At Antioch and at Zion Progressive Baptist Church the mission of restoring congregants to their rightful, dignified place in God’s creation was frequently given to Irene Day (later Irene Day-Comer). The experience of listening to her became a spiritual rite of passage for those of us who were growing up and privileged to hear her sing or give a concert performance. Whether at Sunday morning or evening services, or upon countless special events such as weddings, funerals, or any occasion celebrating the human experience, Irene Day-Comer’s rapturous voice infused spiritual uplift across several generations.

Irene Day-Comer has the unique ability to make her listeners feel that there are only three people in the sacred space of worship – the soloist, the listener, and God. In later years, her stirring renditions of sacred standards have drawn national acclaim. She not only accepts the musical responsibility of transforming lives within the local community, but she also embraces a broader commitment of witnessing to America through song. As a soloist with the Blakely Singers’ National Gospel Tour, in concerts, at political and union rallies, religious conventions, and even national sporting events, and now with her re-mastered 20th-Anniversary release of this CD, Mrs. Day-Comer continues her life’s mission of communicating God’s message through song.

The accolades for Mrs. Day-Comer’s talents span her 70 years as a soloist. Mrs. Day-Comer appeared on programs with the late, great Mahalia Jackson and the famed Barrett Sisters. She received the African Methodist Episcopal Church’s highest honor for contributions to humanity through the arts, and was selected to represent the International United Steelworkers as its ambassador of song, performing the National Anthem at the Las Vegas Hilton in the early 90’s.

As a young woman, Mrs. Day-Comer was offered opportunities to pursue other styles of music but politely declined, preferring sacred music. In recognition of her life-long contributions she has received other awards and acknowledgements, including the Black Expo Award and special recognition from the U.S. Congressional Black Caucus.

The original tape master of this recording, formerly entitled “He’s Everywhere,” was nearly destroyed as a result of 20 years of metallic erosion. Fortunately, the recording was restored through digital technology so that the music of Irene Day-Comer can now be archived in our audio libraries for future generations to enjoy. She can now touch and inspire the world with her great renditions of songs like “Precious Lord,” “Touch Somebody’s Life,” “God So Loved The World,” and “He’s Everywhere.”

Gifted with a rich, lyric soprano voice, a fully two-octave range, and perfect pitch, Irene Day-Comer’s delicate, sweet singing resonates with a personal faith tested by the vagaries of human experience. She conveys the universal message of God’s love as being everywhere and for everyone who seeks, drawing each listener into his or her own personal journey. She persuades us to experience the reality of God’s love as she sings freely and clearly in a combined language of heart, soul, mind, and spirit.

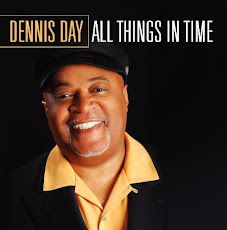

Anchored by the able accompaniment of pianist Marilyn Hairston, this re-mastered recording also features several renowned New York City-based musicians; J.D. Parren on winds, Bob Cunningham on contrabass, and Dr. Gregory Hopkins, tenor-pianist extraordinare. Fresh arrangements are produced and orchestrated by Mrs. Day-Comer’s son, Dennis Day, who also contributes background vocals and was inspired to re-release this recording after the events of September 11, 2001.

Perhaps the legendary Leslie Uggams best sums it up. After listening to this recording, she stated, “In the kind of world that we inhabit today, after September 11, we all need Irene Day-Comer’s music. She takes us back to church, and the songs are performed beautifully.”

Now future generations can enjoy Irene Day-Comer’s unique talent, just as so many have earlier been taken to places of a blessed charity, come Sunday morning, gently reminding us that we, too, can touch somebody’s life.

Saturday, July 14, 2007

Friday, July 6, 2007

Remembering Pookie Hudson, an American Original

On Tuesday evening January 16 I received word that Thornton James "Pookie" Hudson had passed away after a valiant battle against thymus cancer. For music purists and fans of vocal harmony groups who resist allowing Doo Wop to be relegated to America’s cultural margins, the loss is meaningful and symbolizes the passing of a true American cultural icon.

In the 1950s and early 60s, urban youth from Pittsburgh to Paducah gathered under city streetlights on balmy summer evenings to harmonize amidst the neighborhood’s energetic bustle. For any of these groups, one signature song in particular began with the lowest voice booming out a version of the great Gerald Gregory’s quintessential bass line – five universally familiar notes, doht – doh – doht – doht – doht, followed by a lead tenor and chorus echoing the sweet refrain, “Good night, sweetheart, well it’s time to go…” To that early generation, those words signaled lights out…gig’s up…party’s over…mama says come on home. In every street-corner group, the lead singer mimicked one voice – the enormously popular performer known to legions of adoring fans, especially in the African American community, simply as Pookie.

James Pookie Hudson was among my early musical idols – a unique song stylist during the halcyon days of Rhythm and Blues. Aaron Neville, Al Jarreau, Smokey Robinson, and countless balladeers from the Doo-Wop era have affirmed Pookie's influence on their music. As lead singer of the legendary Spaniels, Pookie Hudson was peerless. During the 50s and 60s Pookie’s group routinely played to enthusiastic sold-out audiences at New York’s Apollo, Chicago’s Regal, Washington DC’s Howard, and other major concert halls in Baltimore, Detroit, Philadelphia, Los Angeles, and Europe. The Spaniels were among the earliest Rhythm and Blues vocal groups to appear on Dick Clark's popular nationally syndicated television show, American Bandstand.

In his intriguing biography, Good Night Sweetheart Good Night, renown journalist and social commentator Richard G. Carter chronicles the group’s emergence from the gritty blue-collar neighborhoods of Gary where they won the fabled Gary Roosevelt Talent Show, a forum which was to also prove pivotal for other Gary exports, including Avery Brooks, Denice Williams, and the Jackson Five. Many of these performers went on to become media darlings on radio and television with the aid of mega-labels like Motown’s potent promotions on a radio-friendly hit machine in the post-payola era, while Pookie and the Spaniels became victims of the payola system by their refusal to acquiesce to it, and therefore received far less national airplay than they merited. Nevertheless, Pookie’s silky tenor vibrato pervaded the era of male group leads on the segregated radio airwaves with recordings like “I Know,” “Stormy Weather,” and the chart buster "Good Night Sweetheart,” all perenniel favorites in America's urban centers, but recordings that never gained the tremendous commercial success that many critics today believe they deserved.

I first met Pookie when I was 16 years old. He and his business manager made a surprise visit to my home in East Chicago at the urging of my cousin, who was then his wife. Pookie listened to my high school quartet and, at our prodding, he graciously rendered a stirring, Gospel-tinged acappella version of “Peace of Mind” in our living room. With his face nestled against the wall, Pookie’s rich tenor vibrato, clear as a bell, echoed throughout the room, shimmering and soaring effortlessly with an emotional quality that spoke soul to soul. That day he gave me a prized copy of his latest release, a lushly arranged pop/spiritual ballad with a moral called “Meek Man,” recorded on the fledgling Philadelphia-based Neptune label. Sadly, that record made a meager showing commercially but it remains among my favorites of Pookie’s songs.

Over the years I talked to Pookie by telephone occasionally when he was in California, Gary, or the District of Columbia, where he maintained loyal fan bases. I made a point to take in his Oldies and Doo-Wop performances in the New York City area. I attended the triumphant comeback appearance of Pookie Hudson and the Spaniels at a Rhythm and Blues Revival Show at the Apollo in August 1991 where, after a 30-year hiatus, Pookie’s acapella rendition of “Danny Boy” led to the evening’s only encore performance. Pookie became a mainstay to millions of “old schoolers,” as he was seen frequently on PBS telethon fundraisers, which have discovered the lucrative baby boomer-plus market. Those shows often ended with Pookie’s “Good Night, Sweetheart” as a finale.

Pookie is on record as stating that part of the reason the Spaniels were not played as much on radio stations along the North Eastern corridor’s cities as on radio stations in other areas of the country is that he refused to allow a certain powerful on-air radio Czar and popular disc jockey of the era to sign on as co-publisher of songs he had written, a common but unlawful practice during the payola period of the 1950s. Pookie had many struggles over the years but he refused to fall prey to the economic enslavement that engulfed so many talented Black artist/writers who never saw a dime in royalties in spite of so called sweetheart deals. Such a compromise would ensure that the coauthor/publisher disc jockey would be entitled to a percentage of the songwriter’s royalties in perpetuity. In later years Pookie did pursue a lawsuit against the producers of the blockbuster movie “Three Men and a Baby,” starring Tom Seleck, in which Pookie’s song “Good Night Sweetheart” was illegally featured, constituting copyright infringement. The song was covered by a number of groups, including the popular McGuire Sisters in 1954 whose rendition achieved gold-record status, the highest accolade of the day. The song was covered by a number of groups, including the popular McGuire Sisters in 1954 whose rendition achieved gold-record status, the highest accolade of the day. It was later recorded on the soundtracks of other movies, including “American Graffiti,” and on television, including in a Dodge commercial.Yet it was not until the 1990’s that Pookie began receiving royalties for his song.

I last saw Pookie perform at the Queens Borough Community College on October 21, 2005 in a show billed as a tribute to Pookie. He said he felt good, and that the prostate cancer he had so courageously battled for several years was in remission. In a truly star-studded lineup that included the Teenagers, Johnny Maestro and the Brooklyn Bridge, the Orioles, the Harp Tones, the Flamingoes, the Chantels, Speedo and the Cadillacs, Earl Lewis and the Channels, and other great groups, Pookie and the Spaniels closed the show. The house that night, as it had so many times before, belonged to Pookie Hudson and the Spaniels.

Pookie will be sorely missed by friends, fans, and loved ones but, thank God, his songs will live on forever. Now finally, Pookie, the “Peace of Mind” about which you so movingly sang is yours, and neither you nor your timeless, beautiful songs shall be forgotten.

In the 1950s and early 60s, urban youth from Pittsburgh to Paducah gathered under city streetlights on balmy summer evenings to harmonize amidst the neighborhood’s energetic bustle. For any of these groups, one signature song in particular began with the lowest voice booming out a version of the great Gerald Gregory’s quintessential bass line – five universally familiar notes, doht – doh – doht – doht – doht, followed by a lead tenor and chorus echoing the sweet refrain, “Good night, sweetheart, well it’s time to go…” To that early generation, those words signaled lights out…gig’s up…party’s over…mama says come on home. In every street-corner group, the lead singer mimicked one voice – the enormously popular performer known to legions of adoring fans, especially in the African American community, simply as Pookie.

James Pookie Hudson was among my early musical idols – a unique song stylist during the halcyon days of Rhythm and Blues. Aaron Neville, Al Jarreau, Smokey Robinson, and countless balladeers from the Doo-Wop era have affirmed Pookie's influence on their music. As lead singer of the legendary Spaniels, Pookie Hudson was peerless. During the 50s and 60s Pookie’s group routinely played to enthusiastic sold-out audiences at New York’s Apollo, Chicago’s Regal, Washington DC’s Howard, and other major concert halls in Baltimore, Detroit, Philadelphia, Los Angeles, and Europe. The Spaniels were among the earliest Rhythm and Blues vocal groups to appear on Dick Clark's popular nationally syndicated television show, American Bandstand.

In his intriguing biography, Good Night Sweetheart Good Night, renown journalist and social commentator Richard G. Carter chronicles the group’s emergence from the gritty blue-collar neighborhoods of Gary where they won the fabled Gary Roosevelt Talent Show, a forum which was to also prove pivotal for other Gary exports, including Avery Brooks, Denice Williams, and the Jackson Five. Many of these performers went on to become media darlings on radio and television with the aid of mega-labels like Motown’s potent promotions on a radio-friendly hit machine in the post-payola era, while Pookie and the Spaniels became victims of the payola system by their refusal to acquiesce to it, and therefore received far less national airplay than they merited. Nevertheless, Pookie’s silky tenor vibrato pervaded the era of male group leads on the segregated radio airwaves with recordings like “I Know,” “Stormy Weather,” and the chart buster "Good Night Sweetheart,” all perenniel favorites in America's urban centers, but recordings that never gained the tremendous commercial success that many critics today believe they deserved.

I first met Pookie when I was 16 years old. He and his business manager made a surprise visit to my home in East Chicago at the urging of my cousin, who was then his wife. Pookie listened to my high school quartet and, at our prodding, he graciously rendered a stirring, Gospel-tinged acappella version of “Peace of Mind” in our living room. With his face nestled against the wall, Pookie’s rich tenor vibrato, clear as a bell, echoed throughout the room, shimmering and soaring effortlessly with an emotional quality that spoke soul to soul. That day he gave me a prized copy of his latest release, a lushly arranged pop/spiritual ballad with a moral called “Meek Man,” recorded on the fledgling Philadelphia-based Neptune label. Sadly, that record made a meager showing commercially but it remains among my favorites of Pookie’s songs.

Over the years I talked to Pookie by telephone occasionally when he was in California, Gary, or the District of Columbia, where he maintained loyal fan bases. I made a point to take in his Oldies and Doo-Wop performances in the New York City area. I attended the triumphant comeback appearance of Pookie Hudson and the Spaniels at a Rhythm and Blues Revival Show at the Apollo in August 1991 where, after a 30-year hiatus, Pookie’s acapella rendition of “Danny Boy” led to the evening’s only encore performance. Pookie became a mainstay to millions of “old schoolers,” as he was seen frequently on PBS telethon fundraisers, which have discovered the lucrative baby boomer-plus market. Those shows often ended with Pookie’s “Good Night, Sweetheart” as a finale.

Pookie is on record as stating that part of the reason the Spaniels were not played as much on radio stations along the North Eastern corridor’s cities as on radio stations in other areas of the country is that he refused to allow a certain powerful on-air radio Czar and popular disc jockey of the era to sign on as co-publisher of songs he had written, a common but unlawful practice during the payola period of the 1950s. Pookie had many struggles over the years but he refused to fall prey to the economic enslavement that engulfed so many talented Black artist/writers who never saw a dime in royalties in spite of so called sweetheart deals. Such a compromise would ensure that the coauthor/publisher disc jockey would be entitled to a percentage of the songwriter’s royalties in perpetuity. In later years Pookie did pursue a lawsuit against the producers of the blockbuster movie “Three Men and a Baby,” starring Tom Seleck, in which Pookie’s song “Good Night Sweetheart” was illegally featured, constituting copyright infringement. The song was covered by a number of groups, including the popular McGuire Sisters in 1954 whose rendition achieved gold-record status, the highest accolade of the day. The song was covered by a number of groups, including the popular McGuire Sisters in 1954 whose rendition achieved gold-record status, the highest accolade of the day. It was later recorded on the soundtracks of other movies, including “American Graffiti,” and on television, including in a Dodge commercial.Yet it was not until the 1990’s that Pookie began receiving royalties for his song.

I last saw Pookie perform at the Queens Borough Community College on October 21, 2005 in a show billed as a tribute to Pookie. He said he felt good, and that the prostate cancer he had so courageously battled for several years was in remission. In a truly star-studded lineup that included the Teenagers, Johnny Maestro and the Brooklyn Bridge, the Orioles, the Harp Tones, the Flamingoes, the Chantels, Speedo and the Cadillacs, Earl Lewis and the Channels, and other great groups, Pookie and the Spaniels closed the show. The house that night, as it had so many times before, belonged to Pookie Hudson and the Spaniels.

Pookie will be sorely missed by friends, fans, and loved ones but, thank God, his songs will live on forever. Now finally, Pookie, the “Peace of Mind” about which you so movingly sang is yours, and neither you nor your timeless, beautiful songs shall be forgotten.

Tuesday, July 3, 2007

Congratulations 2007 JazzMobile Vocal Contest Winner

The Jazz Mobile Anheuser Busch Vocal competition, now in its fourth year crowned Alexis Cole as this year's winner.

The sultry alto was judged the best of twelve finalists competing for first place in the annual vocal competition that showcases some of the finest jazz artists on today's scene.Second place honors went to Bonzella Lewis, a charismatic singer/actress and veteran of Broadway's The Wiz and Bubbl'ng Brown Sugar.

Ms. Cole demonstrated a jazz sensibility and style that won over a stellar lineup of judges that included Dr. Billly Taylor, founder of JazzMobile, Thelonious Monk Jr., and Grammy award winning drummer/vocalist Grady Tate.

In addition to the pride that comes with being honored by one's peers, the winner received a $1000 cash prize. Second place honoree Ms. Lewis received a cash prize of $500. As for yours truly, I received dinner for two for having drawn the greatest number of fans and supporters. It's great to be crowned the Best df the Best Jazz Vocalist 2007. And this year's recipients are most deserved. Hey, but it ain't too shabby to be shown a little love now and then either. So hugs, kisses, and my heartfelt thank you to my family, friends, and fans who showed up at the beautiful Alhambra Ballroom to support me during the contest. So I'll continue to sing for my supper these days. Just remember, let nothing or no one steal your song.

The sultry alto was judged the best of twelve finalists competing for first place in the annual vocal competition that showcases some of the finest jazz artists on today's scene.Second place honors went to Bonzella Lewis, a charismatic singer/actress and veteran of Broadway's The Wiz and Bubbl'ng Brown Sugar.

Ms. Cole demonstrated a jazz sensibility and style that won over a stellar lineup of judges that included Dr. Billly Taylor, founder of JazzMobile, Thelonious Monk Jr., and Grammy award winning drummer/vocalist Grady Tate.

In addition to the pride that comes with being honored by one's peers, the winner received a $1000 cash prize. Second place honoree Ms. Lewis received a cash prize of $500. As for yours truly, I received dinner for two for having drawn the greatest number of fans and supporters. It's great to be crowned the Best df the Best Jazz Vocalist 2007. And this year's recipients are most deserved. Hey, but it ain't too shabby to be shown a little love now and then either. So hugs, kisses, and my heartfelt thank you to my family, friends, and fans who showed up at the beautiful Alhambra Ballroom to support me during the contest. So I'll continue to sing for my supper these days. Just remember, let nothing or no one steal your song.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)