(Dr. Geneva Moore is Professor of English Literature, University of Wisconsin, Madison and a dear friend of mine. Here is her tribute to my mother, Irene Day-Comer, and her music. At the left you can click through to hear my mother's recording, Touch Somebody's Life.)

Irene Day: Touch Somebody’s Life (20th Anniversary Edition)

Sunday morning. Every mature African American who attended a Baptist church remembers the sweet, significant meaning of these descriptive words: Sunday morning. On the first day of the week in East Chicago, Indiana, the Antioch Baptist Church provided its members and visitors with a deeper understanding of their identity beyond the limited secular identity imposed upon them by the world.

The spirited goal of Sunday morning was accomplished primarily through the ministry of sermons and music, especially the music of Negro spirituals, invested as they are in a spiritual legacy borne out of the poignant depths of the ancestors’ creative suffering.

From Maya Angelou to Toni Morrison, a select number of African American writers have paid tribute to soloists who performed, in their melodious voices, the necessary Sunday morning ritual of transporting African Americans into a sacred sphere. In this blessed space that literally and figuratively transformed their lives beyond the racial challenges and the tedium of daily life, African American worshippers experienced a weekly rebirth.

At Antioch and at Zion Progressive Baptist Church the mission of restoring congregants to their rightful, dignified place in God’s creation was frequently given to Irene Day (later Irene Day-Comer). The experience of listening to her became a spiritual rite of passage for those of us who were growing up and privileged to hear her sing or give a concert performance. Whether at Sunday morning or evening services, or upon countless special events such as weddings, funerals, or any occasion celebrating the human experience, Irene Day-Comer’s rapturous voice infused spiritual uplift across several generations.

Irene Day-Comer has the unique ability to make her listeners feel that there are only three people in the sacred space of worship – the soloist, the listener, and God. In later years, her stirring renditions of sacred standards have drawn national acclaim. She not only accepts the musical responsibility of transforming lives within the local community, but she also embraces a broader commitment of witnessing to America through song. As a soloist with the Blakely Singers’ National Gospel Tour, in concerts, at political and union rallies, religious conventions, and even national sporting events, and now with her re-mastered 20th-Anniversary release of this CD, Mrs. Day-Comer continues her life’s mission of communicating God’s message through song.

The accolades for Mrs. Day-Comer’s talents span her 70 years as a soloist. Mrs. Day-Comer appeared on programs with the late, great Mahalia Jackson and the famed Barrett Sisters. She received the African Methodist Episcopal Church’s highest honor for contributions to humanity through the arts, and was selected to represent the International United Steelworkers as its ambassador of song, performing the National Anthem at the Las Vegas Hilton in the early 90’s.

As a young woman, Mrs. Day-Comer was offered opportunities to pursue other styles of music but politely declined, preferring sacred music. In recognition of her life-long contributions she has received other awards and acknowledgements, including the Black Expo Award and special recognition from the U.S. Congressional Black Caucus.

The original tape master of this recording, formerly entitled “He’s Everywhere,” was nearly destroyed as a result of 20 years of metallic erosion. Fortunately, the recording was restored through digital technology so that the music of Irene Day-Comer can now be archived in our audio libraries for future generations to enjoy. She can now touch and inspire the world with her great renditions of songs like “Precious Lord,” “Touch Somebody’s Life,” “God So Loved The World,” and “He’s Everywhere.”

Gifted with a rich, lyric soprano voice, a fully two-octave range, and perfect pitch, Irene Day-Comer’s delicate, sweet singing resonates with a personal faith tested by the vagaries of human experience. She conveys the universal message of God’s love as being everywhere and for everyone who seeks, drawing each listener into his or her own personal journey. She persuades us to experience the reality of God’s love as she sings freely and clearly in a combined language of heart, soul, mind, and spirit.

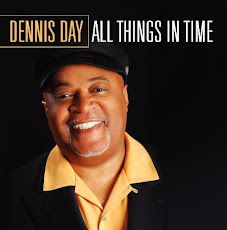

Anchored by the able accompaniment of pianist Marilyn Hairston, this re-mastered recording also features several renowned New York City-based musicians; J.D. Parren on winds, Bob Cunningham on contrabass, and Dr. Gregory Hopkins, tenor-pianist extraordinare. Fresh arrangements are produced and orchestrated by Mrs. Day-Comer’s son, Dennis Day, who also contributes background vocals and was inspired to re-release this recording after the events of September 11, 2001.

Perhaps the legendary Leslie Uggams best sums it up. After listening to this recording, she stated, “In the kind of world that we inhabit today, after September 11, we all need Irene Day-Comer’s music. She takes us back to church, and the songs are performed beautifully.”

Now future generations can enjoy Irene Day-Comer’s unique talent, just as so many have earlier been taken to places of a blessed charity, come Sunday morning, gently reminding us that we, too, can touch somebody’s life.

Saturday, July 14, 2007

Friday, July 6, 2007

Remembering Pookie Hudson, an American Original

On Tuesday evening January 16 I received word that Thornton James "Pookie" Hudson had passed away after a valiant battle against thymus cancer. For music purists and fans of vocal harmony groups who resist allowing Doo Wop to be relegated to America’s cultural margins, the loss is meaningful and symbolizes the passing of a true American cultural icon.

In the 1950s and early 60s, urban youth from Pittsburgh to Paducah gathered under city streetlights on balmy summer evenings to harmonize amidst the neighborhood’s energetic bustle. For any of these groups, one signature song in particular began with the lowest voice booming out a version of the great Gerald Gregory’s quintessential bass line – five universally familiar notes, doht – doh – doht – doht – doht, followed by a lead tenor and chorus echoing the sweet refrain, “Good night, sweetheart, well it’s time to go…” To that early generation, those words signaled lights out…gig’s up…party’s over…mama says come on home. In every street-corner group, the lead singer mimicked one voice – the enormously popular performer known to legions of adoring fans, especially in the African American community, simply as Pookie.

James Pookie Hudson was among my early musical idols – a unique song stylist during the halcyon days of Rhythm and Blues. Aaron Neville, Al Jarreau, Smokey Robinson, and countless balladeers from the Doo-Wop era have affirmed Pookie's influence on their music. As lead singer of the legendary Spaniels, Pookie Hudson was peerless. During the 50s and 60s Pookie’s group routinely played to enthusiastic sold-out audiences at New York’s Apollo, Chicago’s Regal, Washington DC’s Howard, and other major concert halls in Baltimore, Detroit, Philadelphia, Los Angeles, and Europe. The Spaniels were among the earliest Rhythm and Blues vocal groups to appear on Dick Clark's popular nationally syndicated television show, American Bandstand.

In his intriguing biography, Good Night Sweetheart Good Night, renown journalist and social commentator Richard G. Carter chronicles the group’s emergence from the gritty blue-collar neighborhoods of Gary where they won the fabled Gary Roosevelt Talent Show, a forum which was to also prove pivotal for other Gary exports, including Avery Brooks, Denice Williams, and the Jackson Five. Many of these performers went on to become media darlings on radio and television with the aid of mega-labels like Motown’s potent promotions on a radio-friendly hit machine in the post-payola era, while Pookie and the Spaniels became victims of the payola system by their refusal to acquiesce to it, and therefore received far less national airplay than they merited. Nevertheless, Pookie’s silky tenor vibrato pervaded the era of male group leads on the segregated radio airwaves with recordings like “I Know,” “Stormy Weather,” and the chart buster "Good Night Sweetheart,” all perenniel favorites in America's urban centers, but recordings that never gained the tremendous commercial success that many critics today believe they deserved.

I first met Pookie when I was 16 years old. He and his business manager made a surprise visit to my home in East Chicago at the urging of my cousin, who was then his wife. Pookie listened to my high school quartet and, at our prodding, he graciously rendered a stirring, Gospel-tinged acappella version of “Peace of Mind” in our living room. With his face nestled against the wall, Pookie’s rich tenor vibrato, clear as a bell, echoed throughout the room, shimmering and soaring effortlessly with an emotional quality that spoke soul to soul. That day he gave me a prized copy of his latest release, a lushly arranged pop/spiritual ballad with a moral called “Meek Man,” recorded on the fledgling Philadelphia-based Neptune label. Sadly, that record made a meager showing commercially but it remains among my favorites of Pookie’s songs.

Over the years I talked to Pookie by telephone occasionally when he was in California, Gary, or the District of Columbia, where he maintained loyal fan bases. I made a point to take in his Oldies and Doo-Wop performances in the New York City area. I attended the triumphant comeback appearance of Pookie Hudson and the Spaniels at a Rhythm and Blues Revival Show at the Apollo in August 1991 where, after a 30-year hiatus, Pookie’s acapella rendition of “Danny Boy” led to the evening’s only encore performance. Pookie became a mainstay to millions of “old schoolers,” as he was seen frequently on PBS telethon fundraisers, which have discovered the lucrative baby boomer-plus market. Those shows often ended with Pookie’s “Good Night, Sweetheart” as a finale.

Pookie is on record as stating that part of the reason the Spaniels were not played as much on radio stations along the North Eastern corridor’s cities as on radio stations in other areas of the country is that he refused to allow a certain powerful on-air radio Czar and popular disc jockey of the era to sign on as co-publisher of songs he had written, a common but unlawful practice during the payola period of the 1950s. Pookie had many struggles over the years but he refused to fall prey to the economic enslavement that engulfed so many talented Black artist/writers who never saw a dime in royalties in spite of so called sweetheart deals. Such a compromise would ensure that the coauthor/publisher disc jockey would be entitled to a percentage of the songwriter’s royalties in perpetuity. In later years Pookie did pursue a lawsuit against the producers of the blockbuster movie “Three Men and a Baby,” starring Tom Seleck, in which Pookie’s song “Good Night Sweetheart” was illegally featured, constituting copyright infringement. The song was covered by a number of groups, including the popular McGuire Sisters in 1954 whose rendition achieved gold-record status, the highest accolade of the day. The song was covered by a number of groups, including the popular McGuire Sisters in 1954 whose rendition achieved gold-record status, the highest accolade of the day. It was later recorded on the soundtracks of other movies, including “American Graffiti,” and on television, including in a Dodge commercial.Yet it was not until the 1990’s that Pookie began receiving royalties for his song.

I last saw Pookie perform at the Queens Borough Community College on October 21, 2005 in a show billed as a tribute to Pookie. He said he felt good, and that the prostate cancer he had so courageously battled for several years was in remission. In a truly star-studded lineup that included the Teenagers, Johnny Maestro and the Brooklyn Bridge, the Orioles, the Harp Tones, the Flamingoes, the Chantels, Speedo and the Cadillacs, Earl Lewis and the Channels, and other great groups, Pookie and the Spaniels closed the show. The house that night, as it had so many times before, belonged to Pookie Hudson and the Spaniels.

Pookie will be sorely missed by friends, fans, and loved ones but, thank God, his songs will live on forever. Now finally, Pookie, the “Peace of Mind” about which you so movingly sang is yours, and neither you nor your timeless, beautiful songs shall be forgotten.

In the 1950s and early 60s, urban youth from Pittsburgh to Paducah gathered under city streetlights on balmy summer evenings to harmonize amidst the neighborhood’s energetic bustle. For any of these groups, one signature song in particular began with the lowest voice booming out a version of the great Gerald Gregory’s quintessential bass line – five universally familiar notes, doht – doh – doht – doht – doht, followed by a lead tenor and chorus echoing the sweet refrain, “Good night, sweetheart, well it’s time to go…” To that early generation, those words signaled lights out…gig’s up…party’s over…mama says come on home. In every street-corner group, the lead singer mimicked one voice – the enormously popular performer known to legions of adoring fans, especially in the African American community, simply as Pookie.

James Pookie Hudson was among my early musical idols – a unique song stylist during the halcyon days of Rhythm and Blues. Aaron Neville, Al Jarreau, Smokey Robinson, and countless balladeers from the Doo-Wop era have affirmed Pookie's influence on their music. As lead singer of the legendary Spaniels, Pookie Hudson was peerless. During the 50s and 60s Pookie’s group routinely played to enthusiastic sold-out audiences at New York’s Apollo, Chicago’s Regal, Washington DC’s Howard, and other major concert halls in Baltimore, Detroit, Philadelphia, Los Angeles, and Europe. The Spaniels were among the earliest Rhythm and Blues vocal groups to appear on Dick Clark's popular nationally syndicated television show, American Bandstand.

In his intriguing biography, Good Night Sweetheart Good Night, renown journalist and social commentator Richard G. Carter chronicles the group’s emergence from the gritty blue-collar neighborhoods of Gary where they won the fabled Gary Roosevelt Talent Show, a forum which was to also prove pivotal for other Gary exports, including Avery Brooks, Denice Williams, and the Jackson Five. Many of these performers went on to become media darlings on radio and television with the aid of mega-labels like Motown’s potent promotions on a radio-friendly hit machine in the post-payola era, while Pookie and the Spaniels became victims of the payola system by their refusal to acquiesce to it, and therefore received far less national airplay than they merited. Nevertheless, Pookie’s silky tenor vibrato pervaded the era of male group leads on the segregated radio airwaves with recordings like “I Know,” “Stormy Weather,” and the chart buster "Good Night Sweetheart,” all perenniel favorites in America's urban centers, but recordings that never gained the tremendous commercial success that many critics today believe they deserved.

I first met Pookie when I was 16 years old. He and his business manager made a surprise visit to my home in East Chicago at the urging of my cousin, who was then his wife. Pookie listened to my high school quartet and, at our prodding, he graciously rendered a stirring, Gospel-tinged acappella version of “Peace of Mind” in our living room. With his face nestled against the wall, Pookie’s rich tenor vibrato, clear as a bell, echoed throughout the room, shimmering and soaring effortlessly with an emotional quality that spoke soul to soul. That day he gave me a prized copy of his latest release, a lushly arranged pop/spiritual ballad with a moral called “Meek Man,” recorded on the fledgling Philadelphia-based Neptune label. Sadly, that record made a meager showing commercially but it remains among my favorites of Pookie’s songs.

Over the years I talked to Pookie by telephone occasionally when he was in California, Gary, or the District of Columbia, where he maintained loyal fan bases. I made a point to take in his Oldies and Doo-Wop performances in the New York City area. I attended the triumphant comeback appearance of Pookie Hudson and the Spaniels at a Rhythm and Blues Revival Show at the Apollo in August 1991 where, after a 30-year hiatus, Pookie’s acapella rendition of “Danny Boy” led to the evening’s only encore performance. Pookie became a mainstay to millions of “old schoolers,” as he was seen frequently on PBS telethon fundraisers, which have discovered the lucrative baby boomer-plus market. Those shows often ended with Pookie’s “Good Night, Sweetheart” as a finale.

Pookie is on record as stating that part of the reason the Spaniels were not played as much on radio stations along the North Eastern corridor’s cities as on radio stations in other areas of the country is that he refused to allow a certain powerful on-air radio Czar and popular disc jockey of the era to sign on as co-publisher of songs he had written, a common but unlawful practice during the payola period of the 1950s. Pookie had many struggles over the years but he refused to fall prey to the economic enslavement that engulfed so many talented Black artist/writers who never saw a dime in royalties in spite of so called sweetheart deals. Such a compromise would ensure that the coauthor/publisher disc jockey would be entitled to a percentage of the songwriter’s royalties in perpetuity. In later years Pookie did pursue a lawsuit against the producers of the blockbuster movie “Three Men and a Baby,” starring Tom Seleck, in which Pookie’s song “Good Night Sweetheart” was illegally featured, constituting copyright infringement. The song was covered by a number of groups, including the popular McGuire Sisters in 1954 whose rendition achieved gold-record status, the highest accolade of the day. The song was covered by a number of groups, including the popular McGuire Sisters in 1954 whose rendition achieved gold-record status, the highest accolade of the day. It was later recorded on the soundtracks of other movies, including “American Graffiti,” and on television, including in a Dodge commercial.Yet it was not until the 1990’s that Pookie began receiving royalties for his song.

I last saw Pookie perform at the Queens Borough Community College on October 21, 2005 in a show billed as a tribute to Pookie. He said he felt good, and that the prostate cancer he had so courageously battled for several years was in remission. In a truly star-studded lineup that included the Teenagers, Johnny Maestro and the Brooklyn Bridge, the Orioles, the Harp Tones, the Flamingoes, the Chantels, Speedo and the Cadillacs, Earl Lewis and the Channels, and other great groups, Pookie and the Spaniels closed the show. The house that night, as it had so many times before, belonged to Pookie Hudson and the Spaniels.

Pookie will be sorely missed by friends, fans, and loved ones but, thank God, his songs will live on forever. Now finally, Pookie, the “Peace of Mind” about which you so movingly sang is yours, and neither you nor your timeless, beautiful songs shall be forgotten.

Tuesday, July 3, 2007

Congratulations 2007 JazzMobile Vocal Contest Winner

The Jazz Mobile Anheuser Busch Vocal competition, now in its fourth year crowned Alexis Cole as this year's winner.

The sultry alto was judged the best of twelve finalists competing for first place in the annual vocal competition that showcases some of the finest jazz artists on today's scene.Second place honors went to Bonzella Lewis, a charismatic singer/actress and veteran of Broadway's The Wiz and Bubbl'ng Brown Sugar.

Ms. Cole demonstrated a jazz sensibility and style that won over a stellar lineup of judges that included Dr. Billly Taylor, founder of JazzMobile, Thelonious Monk Jr., and Grammy award winning drummer/vocalist Grady Tate.

In addition to the pride that comes with being honored by one's peers, the winner received a $1000 cash prize. Second place honoree Ms. Lewis received a cash prize of $500. As for yours truly, I received dinner for two for having drawn the greatest number of fans and supporters. It's great to be crowned the Best df the Best Jazz Vocalist 2007. And this year's recipients are most deserved. Hey, but it ain't too shabby to be shown a little love now and then either. So hugs, kisses, and my heartfelt thank you to my family, friends, and fans who showed up at the beautiful Alhambra Ballroom to support me during the contest. So I'll continue to sing for my supper these days. Just remember, let nothing or no one steal your song.

The sultry alto was judged the best of twelve finalists competing for first place in the annual vocal competition that showcases some of the finest jazz artists on today's scene.Second place honors went to Bonzella Lewis, a charismatic singer/actress and veteran of Broadway's The Wiz and Bubbl'ng Brown Sugar.

Ms. Cole demonstrated a jazz sensibility and style that won over a stellar lineup of judges that included Dr. Billly Taylor, founder of JazzMobile, Thelonious Monk Jr., and Grammy award winning drummer/vocalist Grady Tate.

In addition to the pride that comes with being honored by one's peers, the winner received a $1000 cash prize. Second place honoree Ms. Lewis received a cash prize of $500. As for yours truly, I received dinner for two for having drawn the greatest number of fans and supporters. It's great to be crowned the Best df the Best Jazz Vocalist 2007. And this year's recipients are most deserved. Hey, but it ain't too shabby to be shown a little love now and then either. So hugs, kisses, and my heartfelt thank you to my family, friends, and fans who showed up at the beautiful Alhambra Ballroom to support me during the contest. So I'll continue to sing for my supper these days. Just remember, let nothing or no one steal your song.

Friday, May 25, 2007

Abyssinian Baptist Church and German Martyr: An Influential Link

“When Dietrich Bonhoeffer first attended Harlem’s Abyssinian Baptist Church, it was unlike anything he had ever experienced,” says the Reverend Henry Mitchell. Mitchell is among a host of clergy, scholars, historians, theologians, and former students of Bonhoeffer interviewed in the documentary film Bonhoeffer, directed and produced by Martin Doblmeier in 2004. This film is an important document because it examines a legacy of faith, courage, and costly discipleship.

The film chronicles the life and martyrdom of the German theologian, whose strong opposition to Nazism cost him his life. Bonhoeffer’s faith and heroism, along with his incisive and progressive Christocentric ideas, established him as one of the most influential and compelling Christian philosophers of the modern era.

Bonhoeffer traveled to New York City in the summer of 1930 to pursue further theological training, arriving in the U.S. as Adolph Hitler was beginning his rise to power in Germany. While on a post-doctoral teaching fellowship at Union Theological Seminary, Bonhoeffer was mentored by Rheinhold Niebhur. Niebhur is regarded by many as the father of modern social ethics and he drew widely from the writings and essays of Black literary figures and social critics of the Harlem Renaissance era. Niebhur’s influence on Bonhoeffer broadened Bonhoeffer’s views on the role of Christianity and the Church in the world.

Nowhere is Bonhoeffer’s capacity for embracing a more ecumenical worldview made more profoundly apparent than in his description of his initial encounter with the Black Church in America. Bonhoeffer was introduced to the Abyssinian Baptist Church in Harlem by an African American fellow seminarian, Franklin Fisher. At Abyssinian he found the marriage of the sacred and the political highly appealing.

The preaching and social commitment of Adam Clayton Powell Senior had a powerful effect on Bonhoeffer. His diary entry in the summer of 1931 reads, “In contrast to the didactic style of White churches, I believe that the Gospel in Black Churches truly preaches the Black Christ. The Black Christ is preached with rapturous passion and vision.”

These emotional elements of worship, combined as they were with uncompromised commitment to the Bible, were apparently foreign to Bonhoeffer’s prior religious experience, and they had a profound effect on expanding his sense of the possibilities and breadth of the Gospel as the bedrock of social justice. Bonhoeffer saw parallels to oppressed Black Americans and the Jews of Germany and he gained an even deeper perspective on the true meaning of Sanctorum Communio (the Beloved Community).

Bonhoeffer even taught Sunday School at Abyssinian and cultivated a deep appreciation of Negro spirituals. He approached worship at Abyssinian with deep humility. Later he would bring recordings of his favorite spirituals back to Germany and incorporate what his colleagues deemed these “strange” songs tinged with African rhythms and folkloric sensibilities into his worship and teaching at the seminary he helped to found in Finkenwald. Testimonials in the film by former students and congregants give an indication of the depth of the influence Black religious experience held over his ministry in Germany.

After his return from New York, family members and former students say his preaching was like none they had ever heard. The confluence of Christian social activism as evinced by the dynamic example of Adam Clayton Powell Senior, fused with Bonhoeffer’s own deductions (influenced by Neibhur) helped to crystallize his personal theology of Christocentric ethics. Ultimately, he concluded that “the will of God is not a set of rules, but requires examination of every situation as an act of faith.” For Bonhoeffer, the existential challenge was therefore to forever be engaged with reexamining the will of God.

Doblmeier artfully presents a balanced view of Bonhoeffer’s humanity, revealing his painful dilemmas and occasional errors in judgment, which help to demystify the saintly aura generally ascribed to this highly venerated theologian. We watch Bonhoeffer struggle with his own personal conflicts – his desire for a pastoral vocation, a burgeoning romance, and a predelection for the monastic, contemplative life. In his diary, he anguishes over his decision to refuse to preach at the funeral of his beloved twin sister’s Jewish father-in-law. Bonhoeffer writes of the shame of his fear, after succumbing to the advice of friends who warned him against participating in the funeral for fear of Nazi retaliation and the risk of losing the burgeoning career and ministry that he had so carefully planned. Expression of this sense of shame at having failed to meet a moral challenge allows the viewer to glimpse the man in a moment of epiphany – he senses his own human limitations and failings, but affirms his hope in the power of redemption. Through these rare glimpses the film offers perceptive hints into Bonhoeffer’s inner life as one whose spiritual quest is propelled by a desire to affirm his faith in the will of God over reason and pragmatism.

As I viewed the film, I was struck by the similarities between Dietrich Bonhoeffer and the American Civil Rights leader Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Both men were raised in nurturing upper middle-class families and each was an early college entrant and recipient of the Ph.D degree before the age of 30. Both men were theological activists whose radical commitment to Christianity caused the tragic end to their lives, each at the age of 39. Each man applied his understanding of how activism and faith can be lived out in a world alienated by the fear of difference. With xenophobia as the evil scourge, Naziism for Bonhoeffer became the antithesis of his notion of Sanctorum Communio, while racism in the U.S. undermined the establishment of King’s vision of the Beloved Community.

In their respective roles as moral leaders against the tide of crushing anti-Semitism and racial hatred, each possessed a Herculean capacity to synthesize existential truth from a range of intellectual resources found in their social contexts. Bonhoeffer, who would become a Lutheran pastor and covert activist, and King, who would be an ordained Baptist minister and proponent of nonviolence, each used different means to confront social evil. Bonhoeffer, in his evolution as the conspirators’ moral conscience, sought out Mahatmas Ghandi as his spiritual sage. His New York experience in a predominantly Black Harlem Church helped to conflate his Christocentric and social justice beliefs into covert Christian activism. King’s nonviolent pacifism for the American of African descent, also informed largely by Ghandi’s teaching, proved a useful political construct in bolstering the Black American’s struggle for social justice using nonviolent means.

The exegesis and theological underpinnings absorbed from classical teachings of modern social philosophers like Hegel, Kant, and Niebhur must have impacted strongly on each man. The film, however, fails to adequately examine Bonhoeffers’ moral conclusions, which did compel him to conspire to participate in an assassination attempt on Adolph Hitler’s life in an effort to destroy an evil regime.

If comparisons are to be made between Bonhoeffer and King for purposes of contemporary reference, subsequent character analysis must offer a deeper insight into each man’s reasoning and the formative experiences that shaped him. As avowed men of Christian faith each acted in concert with his belief system, centered on redemption and reconciliation with God, and in the desire to do God’s will. For Bonhoeffer, the end seemed to justify the means, at least with respect to eradicating the evil of Nazism. As a conspirator, Bonhoeffer did not deem acts of duplicity, including deception and murder, sinful. Rather, he saw them as obligatory acts designed to restore moral and spiritual order to a fragmented society. Conversely, Dr. King averred that war and violence are seldom justifiable and must be rejected as a means in the struggle for social justice.

Doblemeier strongly infers that the contemporary activism of Harlem’s Adam Clayton Powell Senior had a significant impact on Bonhoeffer’s emerging activism to thwart Nazism. Although the Doblemeier film accurately characterizes Bonhoeffer’s excursions between Germany and New York, it falls short of developing insight into the formative aspects of his profound experience in the Black church. Bonhoeffer’s sojourn in America, during which he taught Sunday School and worshipped at Harlem’s Abyssinian Baptist Church, are treated as mere educational and cultural diversions instead of being characterized as the near-epiphany experiences that he later describes as “a great liberation.” Many modern-day theologians suggest that the ethos of the Black church deepened Bonhoeffer’s understanding of Christianity as a socially and politically active community of believers. Abyssinian Baptist Church embodied the Sanctorum Communio for Bonhoeffer.

Bonhoeffer was executed on April 9, 1945, a few short months before the end of World War II, for his pivotal role in the Nazi resistance and in a botched assassination attempt on Adolf Hitler.

As the Abyssinian Baptist Church embarks upon its bicentennial celebration, Abyssinian 200, indeed the world may be reminded of this Harlem church’s global impact and influence.

(At left, see video of Dr. Cornel West's comments on Bonhoeffer and Abyssinian.)

Copyright 2007 D-Day Media Group

The film chronicles the life and martyrdom of the German theologian, whose strong opposition to Nazism cost him his life. Bonhoeffer’s faith and heroism, along with his incisive and progressive Christocentric ideas, established him as one of the most influential and compelling Christian philosophers of the modern era.

Bonhoeffer traveled to New York City in the summer of 1930 to pursue further theological training, arriving in the U.S. as Adolph Hitler was beginning his rise to power in Germany. While on a post-doctoral teaching fellowship at Union Theological Seminary, Bonhoeffer was mentored by Rheinhold Niebhur. Niebhur is regarded by many as the father of modern social ethics and he drew widely from the writings and essays of Black literary figures and social critics of the Harlem Renaissance era. Niebhur’s influence on Bonhoeffer broadened Bonhoeffer’s views on the role of Christianity and the Church in the world.

Nowhere is Bonhoeffer’s capacity for embracing a more ecumenical worldview made more profoundly apparent than in his description of his initial encounter with the Black Church in America. Bonhoeffer was introduced to the Abyssinian Baptist Church in Harlem by an African American fellow seminarian, Franklin Fisher. At Abyssinian he found the marriage of the sacred and the political highly appealing.

The preaching and social commitment of Adam Clayton Powell Senior had a powerful effect on Bonhoeffer. His diary entry in the summer of 1931 reads, “In contrast to the didactic style of White churches, I believe that the Gospel in Black Churches truly preaches the Black Christ. The Black Christ is preached with rapturous passion and vision.”

These emotional elements of worship, combined as they were with uncompromised commitment to the Bible, were apparently foreign to Bonhoeffer’s prior religious experience, and they had a profound effect on expanding his sense of the possibilities and breadth of the Gospel as the bedrock of social justice. Bonhoeffer saw parallels to oppressed Black Americans and the Jews of Germany and he gained an even deeper perspective on the true meaning of Sanctorum Communio (the Beloved Community).

Bonhoeffer even taught Sunday School at Abyssinian and cultivated a deep appreciation of Negro spirituals. He approached worship at Abyssinian with deep humility. Later he would bring recordings of his favorite spirituals back to Germany and incorporate what his colleagues deemed these “strange” songs tinged with African rhythms and folkloric sensibilities into his worship and teaching at the seminary he helped to found in Finkenwald. Testimonials in the film by former students and congregants give an indication of the depth of the influence Black religious experience held over his ministry in Germany.

After his return from New York, family members and former students say his preaching was like none they had ever heard. The confluence of Christian social activism as evinced by the dynamic example of Adam Clayton Powell Senior, fused with Bonhoeffer’s own deductions (influenced by Neibhur) helped to crystallize his personal theology of Christocentric ethics. Ultimately, he concluded that “the will of God is not a set of rules, but requires examination of every situation as an act of faith.” For Bonhoeffer, the existential challenge was therefore to forever be engaged with reexamining the will of God.

Doblmeier artfully presents a balanced view of Bonhoeffer’s humanity, revealing his painful dilemmas and occasional errors in judgment, which help to demystify the saintly aura generally ascribed to this highly venerated theologian. We watch Bonhoeffer struggle with his own personal conflicts – his desire for a pastoral vocation, a burgeoning romance, and a predelection for the monastic, contemplative life. In his diary, he anguishes over his decision to refuse to preach at the funeral of his beloved twin sister’s Jewish father-in-law. Bonhoeffer writes of the shame of his fear, after succumbing to the advice of friends who warned him against participating in the funeral for fear of Nazi retaliation and the risk of losing the burgeoning career and ministry that he had so carefully planned. Expression of this sense of shame at having failed to meet a moral challenge allows the viewer to glimpse the man in a moment of epiphany – he senses his own human limitations and failings, but affirms his hope in the power of redemption. Through these rare glimpses the film offers perceptive hints into Bonhoeffer’s inner life as one whose spiritual quest is propelled by a desire to affirm his faith in the will of God over reason and pragmatism.

As I viewed the film, I was struck by the similarities between Dietrich Bonhoeffer and the American Civil Rights leader Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Both men were raised in nurturing upper middle-class families and each was an early college entrant and recipient of the Ph.D degree before the age of 30. Both men were theological activists whose radical commitment to Christianity caused the tragic end to their lives, each at the age of 39. Each man applied his understanding of how activism and faith can be lived out in a world alienated by the fear of difference. With xenophobia as the evil scourge, Naziism for Bonhoeffer became the antithesis of his notion of Sanctorum Communio, while racism in the U.S. undermined the establishment of King’s vision of the Beloved Community.

In their respective roles as moral leaders against the tide of crushing anti-Semitism and racial hatred, each possessed a Herculean capacity to synthesize existential truth from a range of intellectual resources found in their social contexts. Bonhoeffer, who would become a Lutheran pastor and covert activist, and King, who would be an ordained Baptist minister and proponent of nonviolence, each used different means to confront social evil. Bonhoeffer, in his evolution as the conspirators’ moral conscience, sought out Mahatmas Ghandi as his spiritual sage. His New York experience in a predominantly Black Harlem Church helped to conflate his Christocentric and social justice beliefs into covert Christian activism. King’s nonviolent pacifism for the American of African descent, also informed largely by Ghandi’s teaching, proved a useful political construct in bolstering the Black American’s struggle for social justice using nonviolent means.

The exegesis and theological underpinnings absorbed from classical teachings of modern social philosophers like Hegel, Kant, and Niebhur must have impacted strongly on each man. The film, however, fails to adequately examine Bonhoeffers’ moral conclusions, which did compel him to conspire to participate in an assassination attempt on Adolph Hitler’s life in an effort to destroy an evil regime.

If comparisons are to be made between Bonhoeffer and King for purposes of contemporary reference, subsequent character analysis must offer a deeper insight into each man’s reasoning and the formative experiences that shaped him. As avowed men of Christian faith each acted in concert with his belief system, centered on redemption and reconciliation with God, and in the desire to do God’s will. For Bonhoeffer, the end seemed to justify the means, at least with respect to eradicating the evil of Nazism. As a conspirator, Bonhoeffer did not deem acts of duplicity, including deception and murder, sinful. Rather, he saw them as obligatory acts designed to restore moral and spiritual order to a fragmented society. Conversely, Dr. King averred that war and violence are seldom justifiable and must be rejected as a means in the struggle for social justice.

Doblemeier strongly infers that the contemporary activism of Harlem’s Adam Clayton Powell Senior had a significant impact on Bonhoeffer’s emerging activism to thwart Nazism. Although the Doblemeier film accurately characterizes Bonhoeffer’s excursions between Germany and New York, it falls short of developing insight into the formative aspects of his profound experience in the Black church. Bonhoeffer’s sojourn in America, during which he taught Sunday School and worshipped at Harlem’s Abyssinian Baptist Church, are treated as mere educational and cultural diversions instead of being characterized as the near-epiphany experiences that he later describes as “a great liberation.” Many modern-day theologians suggest that the ethos of the Black church deepened Bonhoeffer’s understanding of Christianity as a socially and politically active community of believers. Abyssinian Baptist Church embodied the Sanctorum Communio for Bonhoeffer.

Bonhoeffer was executed on April 9, 1945, a few short months before the end of World War II, for his pivotal role in the Nazi resistance and in a botched assassination attempt on Adolf Hitler.

As the Abyssinian Baptist Church embarks upon its bicentennial celebration, Abyssinian 200, indeed the world may be reminded of this Harlem church’s global impact and influence.

(At left, see video of Dr. Cornel West's comments on Bonhoeffer and Abyssinian.)

Copyright 2007 D-Day Media Group

Wednesday, May 16, 2007

Harlem’s Abyssinian Baptist Church Celebrates 200 Years of Witness and Progress

On Tuesday, May 15, 2007, the Rev. Dr. Calvin O. Butts III, pastor of the nationally renown Abyssinian Baptist Church, announced an 18-month Bicentennial Celebration for the historic institution, adopting as its bicentennial theme Abyssinian 200: True to Our God, True to Our Native Land. New York City mayor Michael Bloomberg proclaimed the day Abyssinian Baptist Church Day and New York State’s top elected officials, Governor Elliot Spitzer, Senator Hillary Clinton, and Congressman Charles Rangel sent special acknowledgements via teleconference wide-screen. The events being planned for the bicentennial will highlight the church’s remarkable spiritual, social, and political contributions that have changed the cultural landscape of America and impacted the world.

Organized in 1808, Abyssinian Baptist Church was founded as a result of disaffection felt by African American and Ethiopian congregants of the First Baptist Church in lower Manhattan, who rejected the segregated worship services and white supremacist practices that prevailed during that period. In the ensuing years, Abyssinian’s worship sites have traversed much of Manhattan, including lower Manhattan and Greenwich Village during the Civil War years, and eventually settling for a time in midtown Manhattan in what is today Times Square.

In 1923, under the leadership of the Reverend Dr. Adam Clayton Powell Sr., the church purchased property on 138th Street between Lenox and Seventh Avenues. Its growing membership flourished, becoming one of the largest Protestant congregations in America with slightly more than14,000 congregants. The Reverend Dr. Butts is the church’s eighth Executive Pastor in a succession of imminent spiritual leaders, including Dr. Samuel DeWitt Proctor, who have led Abyssinian, from its nascent days during slavery into the 21st century to the forefront as an institutional catalyst and model for the spiritual, social, economic, and political aspirations of persons of African descent. Reverend Butts received national attention in 1993 when he led a demonstration in response to offensive and negative lyrics in hip-hop music, publicly dramatizing the issue by driving a steam roller over a pile of hip-hop CDs and cassette tapes.

“Abyssinian 200 is a milestone that represents the continuous role of the African American church as a galvanizing force in the building of beloved communities,” said Reverend Butts on Tuesday. “Through spiritual edification, social justice, political activism, and economic empowerment, the Abyssinian Baptist Church and all churches doing similar work have been sustained leaders of spiritual transformation in the context of real world issues. These issues include housing, education, culture and the arts, family tradition, and ownership of capital.”

The church’s bicentennial organizers hope to ignite a spirit of empowerment and renewed appreciation of African American culture, which many feel has been distorted and misrepresented in recent years. Dr. Howard Dodson, Executive Director of the newly renovated Schomberg Center for the Study and Research of Black Culture and a member of the advisory committee for Abyssinian 200 stated that “The Black church has been and is the center of the Black Community. However, not all African American churches have been as committed to the social, political and economic development of African American people as has Abyssinian since its move to Harlem in 1923 in the midst of the Harlem Renaissance under Reverend Adam Clayton Powell Sr.….The origins of the modern Civil Rights Movement arguably began at Abyssinian in the ’30s and extended into the ’50s under Adam Clayton Powell Jr., the flamboyant City Councilman who became Harlem’s first Black Congressman, and whom many regard as one of the most productive legislators in the history of Congress.

The epochal events planned for Abyssinian 200 have garnered support from national political and cultural leaders and dignitaries. Dr. Maya Angelou and Dr. Cornel West, along with several other nationally recognized scholars, will contribute to a book entitled Witness: Two Centuries of African American Faith and Practice at Abyssinian Baptist Church of Harlem. Jazz great Wynton Marsalis has been commissioned to develop a special Jazz at Lincoln Center orchestral performance with mass choir and guest artists.

In remarks on Tuesday to the 400 in attendance at the press conference, Mr. Marsalis, the Executive Director of Jazz at Lincoln Center, explained, “Our music is so rich, songs like ‘Go Down Moses,’ ‘There is a Balm in Gilead’….What was in these songs was the depths of our ancestors’ tears. We’re going to spend much time studying and researching the material and it will be performed with heft and intellectual weight and integrity that befits a celebration of 200 years of the Abyssinian Baptist Church. The music will be performed by some of our greatest musicians, many of whom have deep roots in the church. It will be about our lives, and about our great and great, great grandmothers’ and grandfathers’ lives.”

Dr. Cornel West, one of the nation’s most recognizable and influential public intellectuals of this generation, stated that “the celebration of the Black church and the culture of our people is important because what’s being put out there today is not worthy of us as a people.” Dr. West sees the upcoming celebrations as what W.E.B. Dubois termed a “coming together” to appreciate the spiritual strivings of Black people, averring that “this is not an abstract exultation of a name – it is a concrete affirmation of an extraordinary people who believed they could do extraordinary things.”

Reverend Butts said that about 200 Abyssinian members will make a pilgrimage to Ethiopia this fall in honor of the church’s founding members. There will also be an exhibit at the Schomberg Center highlighting the church’s evolution and contributions, which include the establishment of new elementary, intermediate, and secondary schools and the founding of the Abyssinian Development Corporation, a community based, not-for-profit organization responsible for more than $500 million in housing and commercial development in Harlem. For more information, visit www.abyssinian.org.

Copyright D-Day Media Group Inc. 2007

Organized in 1808, Abyssinian Baptist Church was founded as a result of disaffection felt by African American and Ethiopian congregants of the First Baptist Church in lower Manhattan, who rejected the segregated worship services and white supremacist practices that prevailed during that period. In the ensuing years, Abyssinian’s worship sites have traversed much of Manhattan, including lower Manhattan and Greenwich Village during the Civil War years, and eventually settling for a time in midtown Manhattan in what is today Times Square.

In 1923, under the leadership of the Reverend Dr. Adam Clayton Powell Sr., the church purchased property on 138th Street between Lenox and Seventh Avenues. Its growing membership flourished, becoming one of the largest Protestant congregations in America with slightly more than14,000 congregants. The Reverend Dr. Butts is the church’s eighth Executive Pastor in a succession of imminent spiritual leaders, including Dr. Samuel DeWitt Proctor, who have led Abyssinian, from its nascent days during slavery into the 21st century to the forefront as an institutional catalyst and model for the spiritual, social, economic, and political aspirations of persons of African descent. Reverend Butts received national attention in 1993 when he led a demonstration in response to offensive and negative lyrics in hip-hop music, publicly dramatizing the issue by driving a steam roller over a pile of hip-hop CDs and cassette tapes.

“Abyssinian 200 is a milestone that represents the continuous role of the African American church as a galvanizing force in the building of beloved communities,” said Reverend Butts on Tuesday. “Through spiritual edification, social justice, political activism, and economic empowerment, the Abyssinian Baptist Church and all churches doing similar work have been sustained leaders of spiritual transformation in the context of real world issues. These issues include housing, education, culture and the arts, family tradition, and ownership of capital.”

The church’s bicentennial organizers hope to ignite a spirit of empowerment and renewed appreciation of African American culture, which many feel has been distorted and misrepresented in recent years. Dr. Howard Dodson, Executive Director of the newly renovated Schomberg Center for the Study and Research of Black Culture and a member of the advisory committee for Abyssinian 200 stated that “The Black church has been and is the center of the Black Community. However, not all African American churches have been as committed to the social, political and economic development of African American people as has Abyssinian since its move to Harlem in 1923 in the midst of the Harlem Renaissance under Reverend Adam Clayton Powell Sr.….The origins of the modern Civil Rights Movement arguably began at Abyssinian in the ’30s and extended into the ’50s under Adam Clayton Powell Jr., the flamboyant City Councilman who became Harlem’s first Black Congressman, and whom many regard as one of the most productive legislators in the history of Congress.

The epochal events planned for Abyssinian 200 have garnered support from national political and cultural leaders and dignitaries. Dr. Maya Angelou and Dr. Cornel West, along with several other nationally recognized scholars, will contribute to a book entitled Witness: Two Centuries of African American Faith and Practice at Abyssinian Baptist Church of Harlem. Jazz great Wynton Marsalis has been commissioned to develop a special Jazz at Lincoln Center orchestral performance with mass choir and guest artists.

In remarks on Tuesday to the 400 in attendance at the press conference, Mr. Marsalis, the Executive Director of Jazz at Lincoln Center, explained, “Our music is so rich, songs like ‘Go Down Moses,’ ‘There is a Balm in Gilead’….What was in these songs was the depths of our ancestors’ tears. We’re going to spend much time studying and researching the material and it will be performed with heft and intellectual weight and integrity that befits a celebration of 200 years of the Abyssinian Baptist Church. The music will be performed by some of our greatest musicians, many of whom have deep roots in the church. It will be about our lives, and about our great and great, great grandmothers’ and grandfathers’ lives.”

Dr. Cornel West, one of the nation’s most recognizable and influential public intellectuals of this generation, stated that “the celebration of the Black church and the culture of our people is important because what’s being put out there today is not worthy of us as a people.” Dr. West sees the upcoming celebrations as what W.E.B. Dubois termed a “coming together” to appreciate the spiritual strivings of Black people, averring that “this is not an abstract exultation of a name – it is a concrete affirmation of an extraordinary people who believed they could do extraordinary things.”

Reverend Butts said that about 200 Abyssinian members will make a pilgrimage to Ethiopia this fall in honor of the church’s founding members. There will also be an exhibit at the Schomberg Center highlighting the church’s evolution and contributions, which include the establishment of new elementary, intermediate, and secondary schools and the founding of the Abyssinian Development Corporation, a community based, not-for-profit organization responsible for more than $500 million in housing and commercial development in Harlem. For more information, visit www.abyssinian.org.

Copyright D-Day Media Group Inc. 2007

Monday, May 7, 2007

Don Imus and the Gansta Rappers: Viewing Black Women Through the Corporate Male Gaze

For several decades, feminists, cultural and film critics have advanced the notion of a “male gaze.” This idea offers a useful construct for analyzing the case of Don Imus.

Gaze theory argues that European patriarchal entitlement encourages and allows white males the privilege of viewing women primarily as objects of male sexual spectacle. Women are positioned as defenseless under the penetration of the gaze and rendered powerless to reciprocate. They become passive recipients of voyeuristic pleasure derived by more powerful male onlookers. Those who possess the power to gaze are empowered to impute value to women on the basis of sexual appeal determined by subjective male sensory experience. The male gazer assesses a woman’s physical attributes and personal qualities in relation to what he deems sexually and visually pleasurable.

Historically in America, Caucasian women have been venerated atop the gaze’s pecking order and accorded the highest social esteem and worth. Conversely, black women have had to overcome a historical legacy of being commodified as chattel property during their enslavement.

The recent Don Imus incident offers a telling glimpse into the role assumed by the corporate mainstream media’s agents as enablers of the male gaze when black women, in particular, become its focus. Imus and Bernard McGuirk rendered a vivid, public example of the raw male gaze in action when they framed their post-game analysis in language referencing Rutgers’ Scarlet Knights as “hardcore hos,” “nappy-headed hos,” and “Jigaboos” (the latter a demeaning 19th-century slur for persons of African descent).

These racial and sexual insults conjure images of the auction block, where Southern slave masters leeringly examined the breasts of young potential concubines. The late singer-poet Oscar Brown Jr. brilliantly captures the brutal impact of the white male gaze in his classic recording “Bid ‘Em In,” a slave auctioneer’s narrative. Four hundred years ago, plantation owners and slave traders established a caste system that assigned levels of intrinsic value to black women based upon physique, skin tone, hair texture, and degrees to which these features were deemed suitably European or Caucasian.

After generations of legally sanctioned rape, a class of mixed-race “mulattos” emerged. Lighter complexioned black women were often granted privileges and physical proximity to the slave master’s resources as house servants, nannies, and mistresses. Such caste distinctions became a troubling source of tension, fostering divisions and complex social stratification among American blacks that linger today.

In the 18th century, President Thomas Jefferson, himself a slaveholder and founding father, would prove influential in fixing colonial America’s early patriarchal gaze and adding a racial aesthetic. Based upon the pseudo scientific understanding of the period, Jefferson attempted to explain physiological differences among African blacks and between the races. Writing in his Notes on Virginia in 1781, Jefferson argues:

“Whether the black of the negro resides in the reticular membrane between the skin and scarf-skin, or in the scarf-skin itself; whether it proceeds from the colour of the blood, the colour of the bile, or from that of some other secretion, the difference is fixed in nature, and is as real as if its seat and cause were better known to us. And is this difference of no importance? Is it not the foundation of a greater or less share of beauty in the two races?”

Jefferson further suggests that blacks themselves prefer what he called “the more elegant symmetry of form” and “superior beauty” that, in his view, distinguished the white race. From that time forward, spurious biblical interpretations and pseudo scientific claims enabled racist views to gain considerable currency.

By the middle 19th century Social Darwinism was widely accepted by America’s aristocracy, firmly evoking the idea of blacks as a lower form of human species. The patriarchal establishment appropriated Darwin’s thesis to bolster their view of white racial superiority, further reinforcing a social order to legitimize white male entitlement by supporting and institutionalizing a belief in racial segregation and the inferiority of nonwhite races as scientific fact.

In 1900, Charles Carroll’s best-selling book The Negro a Beast or In the Image of God? argued that blacks were classified as a species of ape and therefore had no soul. These racist ideas were widespread and used to justify the oppression and maltreatment of African descendants, who were viewed as sub-human, and to perpetuate the male gaze as the exclusive domain of white patriarchal privilege.

For blacks to return the gaze often meant swift retribution, so black codes of conduct forbade black males the privilege of the sexual gaze. Violation of this code precipitated hundreds of black lynchings and promulgated laws against interracial marriage only repealed in the last few decades. Daring to gaze at the white female form resulted in barbarous death, as in the 1955 case of 16-year-old Emmit Till, who was savagely murdered for allegedly looking and whistling at a southern white woman.

To this day these debunked racial myths have been slow to extinguish, and have shaped the racial disposition of many Americans towards blacks. The power of the white male gaze has historically contributed to entrenched racist attitudes and oppressive social policy in our national life.

Spike Lee’s film School Daze, which includes the sartorial musical number “Jigaboos vs. the Wannabes” to which Imus and friends referred, provides a context for viewing American racial attitudes. By dramatizing subtle aspects of caste and class distinctions among African Americans, Lee’s movie portrays ways in which racial and physical variation, such as skin color, hair texture, body type, and the contour and thickness of a woman’s hips and buttocks are still commonly used by the male gaze to ascribe value.

For black audiences, Imus’s glib remarks and smug attitude of white patriarchal supremacy are as iconic as the ten gallon hat he sports. Imus imposed a value judgment on black women whom he assumed could not return the gaze, and did so for the consumption of his 73% male audience. This should have been a moment of transcendence for women aspiring to achieve another step toward athletic parity in American sport, crowning their hard-won victories on the shoulders of women’s suffrage, Harriet Tubman, Ida B. Wells, the Civil Rights Movement, and promises of Title IX. Instead, a serious athletic contest was reduced to a mere beauty pageant.

Imus and McGuirk concluded that the Tenneessee Volunteers, led by stately Candace Parker and Sydney Spencer, were the “cuter” of the two teams. In a thinly veiled attempt at “humor,” they denigrated the Rutgers players as women flawed physically and morally – as promiscuous and androgynous, likening them to the NBA’s Raptors and Grizzlies.

But the Rutgers coach, Vivian Stringer, and her team stood up and dared to gaze back. By compellingly returning the gaze in a press conference, the Rutgers Scarlet Knights garnered so much public support that corporate media heads feared an unprecedented consumer and advertiser backlash from blacks – a multibillion dollar consumer constituency. Imus’s mindless attempt at racial parody was aptly perceived as a bigoted Freudian slip that would not easily be dismissed by the growing public outcry. So, with financial bottom lines at stake and fear of plummeting network ratings, neither CBS nor MSNBC, who profit hugely from the male gaze, had any choice but to finally banish Mr. Imus from the air waves after decades of his broadcasting the gaze with impunity.

The incident brought considerable attention to a question that was voiced repeatedly in the ensuing days by Imus supporters, bloggers, and media pundits seeking to be perceived as presenting “all sides” to keep audiences titillated. The question was: Why does the black community allow hip hop musicians and black comedians to use the same, and even more incendiary, language with impunity? And that question was always followed by a second: Why is the black community not outraged and not speaking out about these insults to women?

Media personalities like Imus and artists like Snoop Dog and 50 Cent are all extensions of the same corporate male gaze. Ultimately, they garner enormous profits for, and are personally enriched by, the same mainstream media establishment. Their relationship has been a profitable trade-off.

Like Imus, many hip hop and rap musicians are simply reflections of the attitudes of those with responsibility and privilege for creating and mediating the images and content that the public consumes. Media synergy is the glue that allows big media content providers in the network and cable television industry to earn staggering profits as producers, distributors, and promoters of the patriarchal male gaze, positioning women as “hos” and “bitches,” and black people as “niggas.”

Hip hop and rap music boasts higher sales among the 18-to-34-year-old white male demographic than any other musical genre. Corporate radio syndicates and record companies form a complex web of interlocking financial streams, each interdependent on the other, generating enormous profit margins. As long as the formula works, what is being lost or devalued goes unquestioned.

For over a decade, black leaders, including Al Sharpton and Jesse Jackson, have been speaking out and resisting the pernicious messages of conspicuous consumption and misogyny so prevalent in “gangsta rap” and other commercial art forms. But the perception that this is not the case stems from the fact that these protests have not received mainstream media attention, although they have been covered in the minority media. It is not in the financial interests of the large media entities to publicize serious moral criticism of their most profitable assets.

As long as greed, xenophobia, sexploitation, and racism are part of mainstream corporate media’s culture and are buoyed by a historical legacy of patriarchal privilege, rappers will continue to serve as an extension of the gaze. In the end, they may need to ask, reflexively, “Are we not the ones being pimped – out-hustled by our more powerful corporate allies?”

Heretofore impervious to social critique, these large media conglomerates have operated unchecked, uncensored, and unaccountable. Until now they have appeared unwilling to relinquish their exclusive birthright to define and impose the gaze. Locked in a symbiotic profitable arrangement with hip hop and rap artists and the outlets that promote them, each continues to benefit while innocent young black women become viciously stereotyped in America.

This may be slowly changing as women dare to return the gaze by exerting their considerable influence in shaping their own images and narrative as did the Rutgers team. In the end, perhaps the Imus affair has given us just the silver lining our nation so desperately needs – an authentic, long-overdue discussion of our racial legacy and its effects on our national future and well being.

©2007 D-Day Media Group, Inc.

Gaze theory argues that European patriarchal entitlement encourages and allows white males the privilege of viewing women primarily as objects of male sexual spectacle. Women are positioned as defenseless under the penetration of the gaze and rendered powerless to reciprocate. They become passive recipients of voyeuristic pleasure derived by more powerful male onlookers. Those who possess the power to gaze are empowered to impute value to women on the basis of sexual appeal determined by subjective male sensory experience. The male gazer assesses a woman’s physical attributes and personal qualities in relation to what he deems sexually and visually pleasurable.

Historically in America, Caucasian women have been venerated atop the gaze’s pecking order and accorded the highest social esteem and worth. Conversely, black women have had to overcome a historical legacy of being commodified as chattel property during their enslavement.

The recent Don Imus incident offers a telling glimpse into the role assumed by the corporate mainstream media’s agents as enablers of the male gaze when black women, in particular, become its focus. Imus and Bernard McGuirk rendered a vivid, public example of the raw male gaze in action when they framed their post-game analysis in language referencing Rutgers’ Scarlet Knights as “hardcore hos,” “nappy-headed hos,” and “Jigaboos” (the latter a demeaning 19th-century slur for persons of African descent).

These racial and sexual insults conjure images of the auction block, where Southern slave masters leeringly examined the breasts of young potential concubines. The late singer-poet Oscar Brown Jr. brilliantly captures the brutal impact of the white male gaze in his classic recording “Bid ‘Em In,” a slave auctioneer’s narrative. Four hundred years ago, plantation owners and slave traders established a caste system that assigned levels of intrinsic value to black women based upon physique, skin tone, hair texture, and degrees to which these features were deemed suitably European or Caucasian.

After generations of legally sanctioned rape, a class of mixed-race “mulattos” emerged. Lighter complexioned black women were often granted privileges and physical proximity to the slave master’s resources as house servants, nannies, and mistresses. Such caste distinctions became a troubling source of tension, fostering divisions and complex social stratification among American blacks that linger today.

In the 18th century, President Thomas Jefferson, himself a slaveholder and founding father, would prove influential in fixing colonial America’s early patriarchal gaze and adding a racial aesthetic. Based upon the pseudo scientific understanding of the period, Jefferson attempted to explain physiological differences among African blacks and between the races. Writing in his Notes on Virginia in 1781, Jefferson argues:

“Whether the black of the negro resides in the reticular membrane between the skin and scarf-skin, or in the scarf-skin itself; whether it proceeds from the colour of the blood, the colour of the bile, or from that of some other secretion, the difference is fixed in nature, and is as real as if its seat and cause were better known to us. And is this difference of no importance? Is it not the foundation of a greater or less share of beauty in the two races?”

Jefferson further suggests that blacks themselves prefer what he called “the more elegant symmetry of form” and “superior beauty” that, in his view, distinguished the white race. From that time forward, spurious biblical interpretations and pseudo scientific claims enabled racist views to gain considerable currency.

By the middle 19th century Social Darwinism was widely accepted by America’s aristocracy, firmly evoking the idea of blacks as a lower form of human species. The patriarchal establishment appropriated Darwin’s thesis to bolster their view of white racial superiority, further reinforcing a social order to legitimize white male entitlement by supporting and institutionalizing a belief in racial segregation and the inferiority of nonwhite races as scientific fact.

In 1900, Charles Carroll’s best-selling book The Negro a Beast or In the Image of God? argued that blacks were classified as a species of ape and therefore had no soul. These racist ideas were widespread and used to justify the oppression and maltreatment of African descendants, who were viewed as sub-human, and to perpetuate the male gaze as the exclusive domain of white patriarchal privilege.

For blacks to return the gaze often meant swift retribution, so black codes of conduct forbade black males the privilege of the sexual gaze. Violation of this code precipitated hundreds of black lynchings and promulgated laws against interracial marriage only repealed in the last few decades. Daring to gaze at the white female form resulted in barbarous death, as in the 1955 case of 16-year-old Emmit Till, who was savagely murdered for allegedly looking and whistling at a southern white woman.

To this day these debunked racial myths have been slow to extinguish, and have shaped the racial disposition of many Americans towards blacks. The power of the white male gaze has historically contributed to entrenched racist attitudes and oppressive social policy in our national life.

Spike Lee’s film School Daze, which includes the sartorial musical number “Jigaboos vs. the Wannabes” to which Imus and friends referred, provides a context for viewing American racial attitudes. By dramatizing subtle aspects of caste and class distinctions among African Americans, Lee’s movie portrays ways in which racial and physical variation, such as skin color, hair texture, body type, and the contour and thickness of a woman’s hips and buttocks are still commonly used by the male gaze to ascribe value.

For black audiences, Imus’s glib remarks and smug attitude of white patriarchal supremacy are as iconic as the ten gallon hat he sports. Imus imposed a value judgment on black women whom he assumed could not return the gaze, and did so for the consumption of his 73% male audience. This should have been a moment of transcendence for women aspiring to achieve another step toward athletic parity in American sport, crowning their hard-won victories on the shoulders of women’s suffrage, Harriet Tubman, Ida B. Wells, the Civil Rights Movement, and promises of Title IX. Instead, a serious athletic contest was reduced to a mere beauty pageant.

Imus and McGuirk concluded that the Tenneessee Volunteers, led by stately Candace Parker and Sydney Spencer, were the “cuter” of the two teams. In a thinly veiled attempt at “humor,” they denigrated the Rutgers players as women flawed physically and morally – as promiscuous and androgynous, likening them to the NBA’s Raptors and Grizzlies.

But the Rutgers coach, Vivian Stringer, and her team stood up and dared to gaze back. By compellingly returning the gaze in a press conference, the Rutgers Scarlet Knights garnered so much public support that corporate media heads feared an unprecedented consumer and advertiser backlash from blacks – a multibillion dollar consumer constituency. Imus’s mindless attempt at racial parody was aptly perceived as a bigoted Freudian slip that would not easily be dismissed by the growing public outcry. So, with financial bottom lines at stake and fear of plummeting network ratings, neither CBS nor MSNBC, who profit hugely from the male gaze, had any choice but to finally banish Mr. Imus from the air waves after decades of his broadcasting the gaze with impunity.

The incident brought considerable attention to a question that was voiced repeatedly in the ensuing days by Imus supporters, bloggers, and media pundits seeking to be perceived as presenting “all sides” to keep audiences titillated. The question was: Why does the black community allow hip hop musicians and black comedians to use the same, and even more incendiary, language with impunity? And that question was always followed by a second: Why is the black community not outraged and not speaking out about these insults to women?

Media personalities like Imus and artists like Snoop Dog and 50 Cent are all extensions of the same corporate male gaze. Ultimately, they garner enormous profits for, and are personally enriched by, the same mainstream media establishment. Their relationship has been a profitable trade-off.

Like Imus, many hip hop and rap musicians are simply reflections of the attitudes of those with responsibility and privilege for creating and mediating the images and content that the public consumes. Media synergy is the glue that allows big media content providers in the network and cable television industry to earn staggering profits as producers, distributors, and promoters of the patriarchal male gaze, positioning women as “hos” and “bitches,” and black people as “niggas.”

Hip hop and rap music boasts higher sales among the 18-to-34-year-old white male demographic than any other musical genre. Corporate radio syndicates and record companies form a complex web of interlocking financial streams, each interdependent on the other, generating enormous profit margins. As long as the formula works, what is being lost or devalued goes unquestioned.

For over a decade, black leaders, including Al Sharpton and Jesse Jackson, have been speaking out and resisting the pernicious messages of conspicuous consumption and misogyny so prevalent in “gangsta rap” and other commercial art forms. But the perception that this is not the case stems from the fact that these protests have not received mainstream media attention, although they have been covered in the minority media. It is not in the financial interests of the large media entities to publicize serious moral criticism of their most profitable assets.

As long as greed, xenophobia, sexploitation, and racism are part of mainstream corporate media’s culture and are buoyed by a historical legacy of patriarchal privilege, rappers will continue to serve as an extension of the gaze. In the end, they may need to ask, reflexively, “Are we not the ones being pimped – out-hustled by our more powerful corporate allies?”

Heretofore impervious to social critique, these large media conglomerates have operated unchecked, uncensored, and unaccountable. Until now they have appeared unwilling to relinquish their exclusive birthright to define and impose the gaze. Locked in a symbiotic profitable arrangement with hip hop and rap artists and the outlets that promote them, each continues to benefit while innocent young black women become viciously stereotyped in America.

This may be slowly changing as women dare to return the gaze by exerting their considerable influence in shaping their own images and narrative as did the Rutgers team. In the end, perhaps the Imus affair has given us just the silver lining our nation so desperately needs – an authentic, long-overdue discussion of our racial legacy and its effects on our national future and well being.

©2007 D-Day Media Group, Inc.

Thursday, May 3, 2007

Comedian D.L. Hughley Insults Rutger's Team

I was appalled at DL Hughley’s slurs about the Rutgers basketball team on the Tonight Show, Wednesday May 2. (See http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tIqD1GCvedw)

When asked by Jay Leno what he thought of the Don Imus debacle, DLH stated that he felt Imus should not have been fired. This in itself was disappointing but acceptable as his right and privilege. But what added insult to injury was his remark that part of Imus's observation was right. He further intoned that the Rutgers team is in fact a bunch of "ugly and nappy-headed girls."

Hughley furthered his comedy schtick by emphasizing that the Rutgers team are the “ugliest nappy-headed girls" he'd ever seen. Jay Leno seemed a little aghast at DL’s comments and remarked about viewer mail he might receive. But DL Hughley seemed unconcerned – even a bit smug about the matter.

I understand First Amendment rights in the USA, but it would seem to me that an individual who has profited so much from his acceptance by both minority and mainstream media outlets would be more sensitive to the representation of black women. Hughley could have used the moment to extol, as Dr. King observed, the content of their character. But like Imus, he chose to objectify these women from his own biased physical point of view.

Hughley could have used his considerable wit and clout to heal open wounds but instead opted to pour salt on them for the sake of a laugh or two, of which, by the way, there weren’t many. And the laughter heard was of the nervous variety. I usually find Hughley hilarious, but his remarks last night about the Rutgers team were a vicious insult and no different from Imus’s, except DLH did omit the "hos" tag in his contemptuous language.

When asked by Jay Leno what he thought of the Don Imus debacle, DLH stated that he felt Imus should not have been fired. This in itself was disappointing but acceptable as his right and privilege. But what added insult to injury was his remark that part of Imus's observation was right. He further intoned that the Rutgers team is in fact a bunch of "ugly and nappy-headed girls."

Hughley furthered his comedy schtick by emphasizing that the Rutgers team are the “ugliest nappy-headed girls" he'd ever seen. Jay Leno seemed a little aghast at DL’s comments and remarked about viewer mail he might receive. But DL Hughley seemed unconcerned – even a bit smug about the matter.

I understand First Amendment rights in the USA, but it would seem to me that an individual who has profited so much from his acceptance by both minority and mainstream media outlets would be more sensitive to the representation of black women. Hughley could have used the moment to extol, as Dr. King observed, the content of their character. But like Imus, he chose to objectify these women from his own biased physical point of view.

Hughley could have used his considerable wit and clout to heal open wounds but instead opted to pour salt on them for the sake of a laugh or two, of which, by the way, there weren’t many. And the laughter heard was of the nervous variety. I usually find Hughley hilarious, but his remarks last night about the Rutgers team were a vicious insult and no different from Imus’s, except DLH did omit the "hos" tag in his contemptuous language.

Sunday, April 29, 2007

Moyers’ Documentary Examines How the War on Iraq was Spun by Big Media